William Arthur Schryer

b. 16 May 1874

d. 28 Nov 1944

Married: 28 April 1915

Emeline Schryer (nèe Egan)

b. 28 Aug 1883

d. 2 Dec 1953

William Arthur Schryer is next in the direct line of our family; he is Davison Sr.’s oldest child and the second great grandson of Nicholas Schryer and Mary Eastwood. His first profession was as a carriage trimmer (installing upholstery in horse-drawn carriages). He later went to work in the tool and die industry and was trained as a chiropractor; he had a chiropractic office in the attic of the family home at 629 Continental Avenue.

William had eight children with two wives. Our line is descended from his second wife, Emeline Egan. They were married 28 April 1915. See information about the Egans at the end of this section. William Arthur’s first wife, Christina Taylor, died in 1909. She left their children, Davison, age 5, and Margaret, age 3. Emeline raised them. An infant daughter named Audrey Mae predeceased Christina by 8 months. See more information about the Taylors at the end of this section.

Emeline and William met when he came to live as a boarder in the Egan family home on Lincoln Avenue in Detroit. After Francis Egan Sr. died, the family, along with William Arthur’s children, Davison and Margaret, moved to the house on Continental Avenue where they lived for many years. By the 1920 census, their first two children, Audrey Emaline and Francis William, had been born and William Arthur was listed as a laborer working for the Auto Top Company. The couple went on to have three more children: Shirley, Alanson and Howard. Alanson was a twin but Emeline miscarried the twin early in the pregnancy and successfully carried Alanson to term.

Emeline Egan was born to Francis B. Egan and Emmaline (Wright) Egan. Both were Canadian and they immigrated to Detroit as a married couple. Francis became Michigan’s Deputy Secretary of State and this sense of status stayed with the family, particularly with Emeline.

Note the various spellings of “Emeline.” The mother (Emmaline), daughter (Emeline), and granddaughter (Audrey Emaline) each used a different spelling of the name.

Emeline owned two millinery shops before she married. Audrey reported that it was the custom to provide lunch to female employees. Emeline’s mother would prepare the food while the women were working. The women, many of them immigrants, shared recipes. One dish that emerged from this period was hot ketchup, which we make to this day. You can find the recipe in the chapter on Norm and Jan Schryer.

Emeline pronounced the family name “Skrier.” Jeremy Schryer, the Canadian Schryer family record keeper of his generation, reports that this is the French Canadian way to say Schryer. With two Canadian parents, it is not surprising that Emeline would have chosen this pronunciation. Emeline herself was Methodist Episcopalian; Audrey was sure that her mother went to heaven.

Emeline was a lady, not a traditional housewife. She was both prim and proper. She was determined and strong-minded. One of Norm Schryer’s early memories of his grandparents is of Emeline taking William by the ear and dragging him into the attic for deigning to have a second beer. She ruled that house.

Once a week she would dress to the nines to do the family shopping, which always included a trip to Archie’s candy shop. She made and altered all of her children’s clothes. As an older woman, she had a housekeeper and sent out the laundry except for the family’s undergarments.

The house on Continental was two stories and the family rented out the bottom level. The upper level had a kitchen, dining room, living room, three bedrooms, screened front and back porches, a bathroom and an attic. Frank Jr. had one bedroom, Emeline Wright Egan had another, and William and Emeline shared the third. After the children were born – 5 living children in 8 years – William Arthur moved to the attic and Emeline retained the bedroom. The children slept, four seasons a year, on the screened-in back porch. In the winter there would often be a layer of frost over the blankets.

At one time, William’s sister Minnie also lived with the family on Continental. The brother and sister had boarded together as adults at various locations in Flint before William Arthur married. She had an unfortunate marriage. It ended when her husband drove with her to the store and went in for a pack of cigarettes. He left out the back and she never saw him again.

As of 2009, the house on Continental had been torn down for decades. Here is what it looks like today, a set of townhouses in a blighted neighborhood. Ann Lawson drove by the street and afterward realized where she had been but was too afraid to go back for photographs due to the nature of the area.

Frank Egan, Emeline’s brother, never married. In Emeline’s eyes, he could do no wrong. He worked as a house painter and, according to Ann Lawson, was secretary of the painters Local Union No. 67. Down our line of the family we have a story to go with that office. Once, he stopped in a bar when he had the union dues money with him and drank too much. Frank was an alcoholic but his sister wouldn’t allow his drinking in the house so he went out in the evenings. He bragged about having the money, it was stolen from him, and he paid it back over time. The family story is that he never drank after that.

Frank loved his nieces and nephews and doted on them with nightly candy treats after dinner and fancy birthday and Christmas presents. One day, Emeline had finished washing and drying all of the good china after a Sunday supper and had them lying on a table waiting to be put away. A very young Audrey, trying to get her mother’s attention, kept tugging on the tablecloth. Eventually she pulled it off, and all of the dishes right on top of herself. Frank replaced the china. My mother has that china set to this day.

Our stories about Uncle Frank come from Audrey and his namesake Fran, my grandfather. Fran didn’t drink and he didn’t keep alcohol in his home due to his experiences with his Uncle Frank’s alcoholism.

The Progressive Era 1900-1930

Callan, J. (2006). Decades of American history: America in the 1900s and 1910s. New York: Facts on File.

and

Chambers II, J. W. (1992). The tyranny of change: American in the Progressive Era: 1890-1920 (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

and

O’Neal, M. (2005). Decades of American history: America in the 1920s. New York: Facts on File.

The socio-political era that William and Emeline lived in prior to the Depression was known as the Progressive Era (1900-1930). After the rugged fallout for the laboring classes of the laissez faire economic reality of the Gilded Age, many Americans believed it was time for change. They believed that government should be involved in correcting problems of poverty, child labor, excessive business domination, and worker’s rights. A belief that education could improve not only individuals but society at large took hold and spending on education doubled between 1900 and 1910. States began to impose mandatory education laws.

Teddy Roosevelt was the first president of the Progressive Era. He was elected McKinley’s vice-president in 1900 and assumed the presidency when McKinley was assassinated in 1901. He promised every American a “square deal” and was a significant contributor to the policies of the Progressive Era. He put into force the Sherman Anti-trust Act, which, while enacted in 1890, had never been enforced.

William and Emeline married on 28 April 1915. At that time, middle- and upper-class white families were not reproducing at rates necessary to sustain themselves in the population. Theodore Roosevelt referred to it as “race suicide.” There was increasing fear about immigration and how it was changing the United States. Laws limiting immigration from some areas of Europe and ceasing immigration from China were implemented.

The rate at which women held jobs outside their homes jumped with industrialization. Before that, the most common form of “women’s work” was as domestic servants. By 1919, more than one quarter of women in the work force were, or had been, married. In addition, levels of educational attainment for women approached that of men for the first time. We can see the results of these trends in our own family. Emeline owned her own business and put off marriage and childbearing until the age of 31.

Among many successes in the world of business during the Progressive Era, Henry Ford revolutionized the mechanization of industry and brought the cost of his Model T Ford into the price range of many American households. Famously, he paid his workers $5 a day (average salaries for working class men in America were approximately $5 per week). Then they, too, could afford a Model T. And labor strife began almost immediately.

The Roaring 20s

Drowne, K., & Huber, P. (2004). American popular culture through history: The 1920s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

This period was also known as the Roaring 20s. America was experiencing economic prosperity, a loosening of social mores, and the development of many modern-day conveniences. “During the 1920s, refrigerators, electric appliances, indoor bathrooms, and hot and cold running water became increasingly common household features, especially in urban areas” (Drowne and Huber, p. 18).

Some Americans were concerned with specific issues, such as women’s suffrage (Amendment 19 to the U.S. constitution, instituted 1919). Other concerns about women’s rights and lives came to the national fore as well. The Comstock Law of 1873 had made it illegal to disseminate information about birth control, even by doctors. A woman named Margaret Sanger took on a life of work to educate women about birth control. “In 1917, Sanger formed the National Birth Control League to organize the national fight for birth control. This organization would later become Planned Parenthood” (Callan, p. 83).

The 1920s was also the generation of flappers – a model of women who rejected the mores of Victorianism, bobbed their hair, wore short skirts, danced, and generally enjoyed themselves just as the nation was enjoying its economic prosperity. While most women of the 1920s still “settled down” and married, many young women did break the mold of their mothers and grandmothers, at least during their youths. After more permissive divorce laws were passed in the 1920s, the divorce rate jumped from 8% to 16.6%. The U.S. had the highest divorce rate in the world (Mintz and Kellogg).

The 1920s was also the period of Prohibition (Amendment 18, instituted 1919, repealed 1933 by the 21st Amendment). During Prohibition, “the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol for consumption” was banned. Many states had already implemented such laws before the national amendment passed. The decade of Prohibition invited, and even celebrated, organized crime. It was personified by Al Capone of the mafia and Eliot Ness of the FBI whose agents were known as The Untouchables (so named because they held the reputation of being incorruptible). Black market alcohol dealers were commonly known as “bootleggers” due to the practice of hiding flasks of alcohol in tall boots. Alcohol flowed into the country from Canada and was also produced here in great quantities.

Family Life

Calvert, Karin. “Children in the house, 1890-1930.” In American home life, 1880-1930: A social history of spaces and services, edited by Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth, 75-93. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

and

Callan, J. (2006). Decades of American history: America in the 1900s and 1910s. New York: Facts on File.

and

Mintz, Steven, and Susan Kellogg. Domestic revolutions: A social history of American family life. New York: Collier Macmillan, 1988.

Trends in child rearing practices of the Progressive Era focused on personality formation. The educational theories of Maria Montessori (The Montessori Method, 1912) and John Dewey (Democracy and Education, 1916) came to the fore stressing the support of independence and curiosity in children. Experts recommended greater permissiveness and the practice of rewarding positive behavior and discouraging negative behavior. Flexible schedules centering on infants and children’s individual needs were popular with child care experts. Previously viewed “problem behaviors” such as thumb sucking and temper tantrums became viewed as normal stages of childhood development.

As the level of education for young children rose, so did the reading material available for them. Classics of the era include the Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), and The Secret Garden (1911). In 1906, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew mysteries series began publication by the wildly successful publisher Edward Stratemeyer. Sunday comics for children also evolved during this period.

Importantly, men’s role as breadwinner began to outpace his role as moral center of the family.

The Depression

William and Emeline weathered the Depression with their five children – aged 5 through 13 in 1929 – and Emeline’s mother and brother Frank. William worked throughout the Depression, often menial jobs for $1 a day, and the family was able to keep their home on Continental Avenue. It was at this time that William went to chiropractic school.

Remnants of the Egan status were retained. The family ate potatoes and beans bought in 20 pound bags with a fully set table including a multitude of proper eating utensils, side and salad dishes, serving pieces and linen napkins in silver napkin rings.

One simple recipe that Emeline served was cooked beans. She soaked navy beans in water over night and in the morning added fresh water, salt pork and onion, and cooked them on low heat until supper time. Alanson’s wife Alice cooked many of Emeline’s recipes, including this one. Carol recalls her and her siblings were barely able to get it down, even soaked in ketchup.

Audrey remembered the end of the Depression for her family. William inherited quite a bit of money when the last of his aunts and uncles died and the farm house was sold. William wanted to buy a new house but Emeline refused. Instead, the family bought a car and William and Emeline took a driving vacation to Mexico.

William Arthur’s Children

William brought two children to his marriage with Emeline – Davison and Margaret. William and Emeline went on to have five children of their own. Below are stories and records of those children.

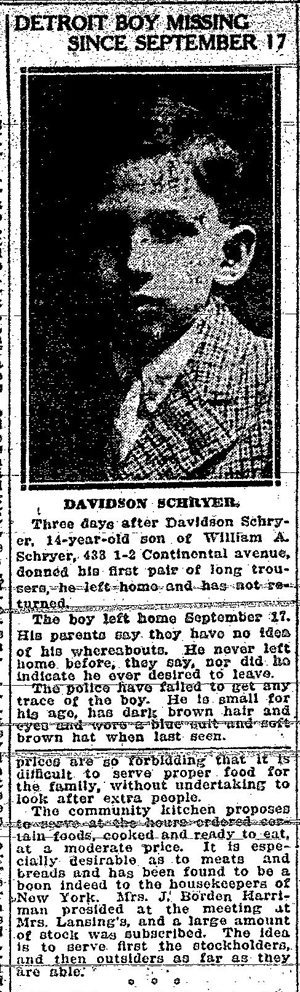

DAVISON TAYLOR SCHRYER

William was extremely hard on Davison. Emeline, seeing William’s behavior with Davison, told him that she would call the police if she disapproved of how he behaved toward her (their) children.

Davison left home in 1918, three days after he turned 14, and eventually went to fight in WWI. What he did between the time he ran away and the time he joined the army is unknown. He was not willing to discuss his youth with his own family when he was an adult.

See the following article from the Detroit Free Press Sep 29, 1918. p. 6 (1 pp.):

According to Davison’s daughter-in-law, Laura Schryer, Davison served overseas in the army in World War I and was then sent to Fort Stanton in New Mexico to recover from tuberculosis. He married Edith Hightower on 12 Dec 1926 and they had two children, George and Geraldine. Edith died in childbirth in 1939 and Davison later remarried to Johnny Davis. William Arthur and Emeline went to see Davison and his family in New Mexico and he later sent George a .22 rifle.

Audrey kept in touch with Davison throughout their lives. Davison was a more active family member as an adult. He signed his name in the guest list at Fran and Elaine’s wedding along with so many other family members. According to Carol (Schryer) De Puys, Davison’s daughter Geraldine once came to Detroit for a visit. Davison’s son George wouldn’t have anything to do with the Schryer family.

Davison died by suicide on 29 Jan 1962, after the death of his second wife, and is buried at Angus Cemetery, Lincoln County, New Mexico. I remember a family funeral where Davison’s suicide was revealed to his nieces and nephews nearly thirty years after it happened. Perhaps a dozen family members were eating in a restaurant after the service and the topic of family longevity was raised. We were discussing who had lived to what age and died of what cause. Davison came up and someone said he had died of a heart attack. Aunt Audrey shook her head and said no, he had died by suicide. Her nieces and nephews were shocked and reminded her that she was the one who had told them he died of a heart attack. “Well,” she said in exasperation, “you’re in your 50s now and old enough to know the truth.”

Also at that dinner I asked Audrey why her mother had married. Emeline and William were not a love match. According to what Audrey told my mother Diane, Emeline owned two millinery shops and did not need to marry for financial reasons. She lived with her family in a secure environment and did not need to marry for a “home of her own.” Audrey looked at me as though I hadn’t thought my question through. “To have children, of course,” she said. Ah, yes, children. The reason we’re all here.

Note from author: Despite your rough upbringing, and your ugly death, Davison, I hope you had a good life after the poor one our family afforded you. I hope you had more than your fair share of joyful moments. More than your fair share of peace. More than your fair share of simple, fatherly happiness with your own children. I hope you escaped your upbringing. I hope you escaped your family, even though they are mine as well.

MARGARET

Margaret was especially close to her step-mother Emeline who exclaimed how lucky she was to get such a beautiful 5-year-old step-daughter when she married William. Margaret was also very close to her half siblings, particularly Audrey and Alanson, as well as her nieces and nephews. Both Alanson and Fran went to live for a summer with Margaret and her husband Chris. For a time Margaret and Chris lived in Hillsdale. She has the family reputation of being an especially kind and gentle lady, liked by everyone. Chris worked at the same factory as Fran did in Hillsdale.

Above is the family’s Christmas photo from 1944. Their boys are James, William and Bob. For years, Bob and James owned their own company in Hillsdale that, among other things, oiled the dirt roads in the community. Bob has died. William is in the financial industry.

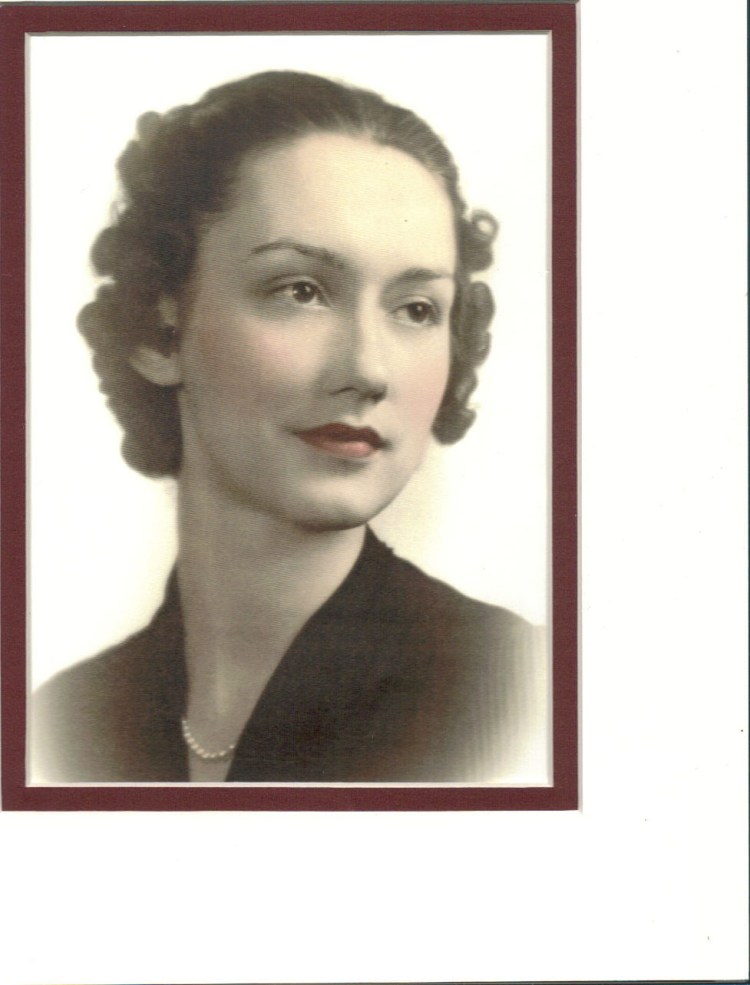

AUDREY EMALINE 17 March 1916 – 22 April 2001

Audrey passed down a great deal of family information to her nieces Carol and Diane. Carol was extremely close to Audrey throughout their lives and Diane went to interview Audrey about the family on several occasions.

One of my favorite stories is one my mother passed down to me. Audrey recalled a time she was at work in the 50s at Parke-Davis, headquartered in Detroit. Once, a male co-worker came over to talk to her. The co-worker put his arm around her. She yelled, loud enough for the entire office to hear: “Keep your God damned hands off me.” No one there ever touched her again.

While some in the family assumed she loved her position in expense accounts at Parke-Davis (a pharmaceutical company), in fact she hated it. One day in her sixties, Aunt Audrey went out on medical leave for gall stones. She didn’t return to work. She took all of her vacation time and left employment. She complained bitterly about her job after retirement. She worked at Parke-Davis from the age of 17 or 18 through retirement and made little money with little status. In the 1970s she was making $4 per hour after approximately 30 years of service. In 2010, according to the Consumer Price Index, this would translate to $15.90 an hour, or $33,072 a year.

Audrey lived in her parent’s home on Continental Avenue until after they had died and she was in her late twenties. Audrey was angry and felt that the burden of caring for her parents had fallen to her. According to her niece Carol, it was Audrey’s choice to stay with her parents. They were independent until the end of their lives.

Audrey chose not to marry. Carol believes Audrey never found a man that lived up to her standards. Once, my mother Diane heard Audrey quip that she never intended to pick up any man’s dirty socks. In any case, Audrey was an independent woman who had the role model of an independent mother.

After moving from the house on Continental, Audrey purchased a condominium at River House, #111, at 8900 E. Jefferson Avenue. Condominiums were a relatively new phenomenon. She lived there until moved into a nursing home before her death. Audrey was appalled as Detroit crumbled around her but she refused to leave. She was the only one of the family to stay in the city throughout its decline. Her condominium would sell today, in 2010, for a mere $4,000 with $380 due monthly for co-operative costs. She would often say, “Look what they have done to my beautiful city.”

Audrey loved children and would allow her nieces and nephews free reign when they came to visit her in her condominium complex. A visit from Aunt Audrey was always greeted with enthusiasm. Alice and Audrey were very close.

Although not a religious person as a young or mature woman, Audrey accepted Christ on her 85th birthday, 17 March, in 2001. Sarah and Sandra, her great nieces, were instrumental in Audrey’s decision. It weighed heavy on their hearts that she was not saved and it was a joyful moment for many people in the family when Audrey accepted Christ.

Audrey did not grow old gracefully. She experienced dementia which was probably Alzheimer’s and had conflict with the family regarding her independence.

FRANCIS WILLIAM 23 July 1917 – 18 June 1961

Francis, my grandfather, was named for his uncle, Emeline’s brother. He was a “blue baby,” and sickly as an infant. He became his grandmother Emmaline’s favorite.

At the age of 16 he graduated from high school and went on to apprentice as a tool and die maker, the same profession as his father. He began to pay rent to his parents but also to save his money.

He was known variously as Fran to his greater family, Frank at work, and Francis to his mother. He has his own chapter later in this book.

SHIRLEY ARLEEN 7 Oct 1920 – June 1991

|

Shirley Arleen (Schryer) Moriarty |

William and Emeline’s third child, Shirley, was born 7 Oct 1920. William and Emeline intended to name her Arleen Shirley and the doctor mildly asked them to consider her initials; hence, Shirley Arleen.

Shirley and Audrey had a serious falling out when Audrey was about 27. As their parents aged, Shirley told Audrey to get out of the house before she spent her adult years taking care of their elderly parents. Audrey, in turn, told Shirley to get out of the house. Shirley did. The sisters had little contact for the rest of their lives.

Shirley was a long-time smoker and died of emphysema in 1991. According to Shirley’s eulogy: Shirley graduated from Southeastern High School in Detroit in 1938 and first worked for the Detroit Library and then for S.S. Kresge & Co. before taking a secretarial position with U.S. Rubber Co. in June of 1939.

Also, from her employer at U.S. Rubber Co. before she left to join the Coast Guard: Her ability to accomplish more than the average person in unusual. Her splendid attitude, and initiative applied to her work is also something not possessed by all people. A Coast Guard Lieutenant said: A highly capable person, far more than just another yeoman assigned to routine duties – considered to be a highly efficient member of the staff, well versed in all her duties of work. In every sense she has replaced a man in the office and has filled the position better than many men rated as Public Relations Specialists. It is in the opinion of this office that subject person is fully qualified for officer training rather than a mere yeoman second class, and would be a distinct credit to the women’s reserve as an officer.

When the war ended Shirley chose to remain in Hawaii and her first civilian job was with the Honolulu Chamber of Commerce. Later, she moved to G.M.A.C. then to the Employers Council and finally to the law firm of Pratt, Tavares & Cassidy where she was very proud to be the private secretary of Attorney Niles Tavares.

On a more personal note, Shirley loved to travel and enjoyed four vacation trips to Europe before her illness began to slow her down.

Shirley became a Coast Guard SPAR during World War II, stationed in Hawaii. She met and married Edwin “Buzz” Moriarty, a resident of the state of Hawaii. They had one child, a son named Michael. According to a letter from Buzz to Alice and Alanson, Michael became a firefighter/paramedic. Michael has two children, Sean and Colleen.

According to this same letter, Shirley’s ashes are in a niche at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Punchbowl Crater. A $200 donation was made to the National Lung Association in Shirley’s name by the bank from which Buzz had retired eight years previously.

Buzz’s letter was very tender; he clearly loved Shirley a great deal.

Shirley returned to the continental United States only a few times after moving to Hawaii, once for her mother’s funeral.

Grandma Elaine, stepping carefully on old family business, asked at Shirley’s death if Audrey would appreciate a sympathy card. Audrey said she felt nothing for her sister and nothing at the death of her sister.

ALANSON ARTHUR 20 Feb 1923 – 4 Aug 1992

William was also very hard on Alanson. Audrey considered her father simply mean. He took it out on his children.

When William wasn’t able to control Alanson as a young man, he tried to instill structure and discipline in him. He sent him to work with the Civilian Conservation Corps planting trees in the Upper Peninsula, a grueling job. “The CCC enrolled 250,000 men between the ages of 18 to 25 … The young men received room and board and $30 a month, $25 of which was sent home to their families” (Callan p. 36). Alice and Alanson went to several weekend-long reunions of men who worked in the CCC and very much enjoyed them.

Alanson went Cass Tech high school for math and machining, which required an entrance exam and was a difficult school to be accepted into. At that time it was a technical school but today it includes the arts. Alanson became a machine and tool maker.

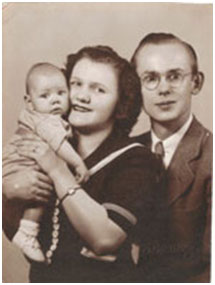

Alanson married Alice Jones on 16 Jan 1943. She was an only child and very happy to marry into a large family. She was particularly close to her sisters-in-law Audrey and Elaine. Alice and Alanson went on to have four children: Carol Alice (born 16 Oct 1948), Gerald (Jerry) (born 7 Dec 1943, died 7 Jan 1981), Alan Frederick (born 24 Sep 1953), and Ronald William (born 8 Jun 1956). The above picture with Jerry as an infant was taken while Alanson was home from boot camp.

William Arthur and Emaline with Alice, holding Jerry, and Shirley, 1943

Alice and Jerry lived part of time during the war with each of the grandparents while Alanson was overseas from 1944-1946. He came home when Jerry was 3.

Alanson was on the front lines in World War II in the infantry, the 90th division in the Army. He served in France and Germany. He was Missing in Action for several months during the war when he lost contact with his company. Alanson was part of the occupation army that liberated the concentration camps, an experience he never talked about. Alice and he went to eight or ten reunions of his division and he enjoyed them very much.

They also enjoyed traveling. They went to Hawaii four or five times, to Jamaica, Aruba, and to Florida many times to visit Aunt Margaret Polkow. Alice was very family-oriented.

Alanson’s first business, a tool and machine shop called Kaul Screw Products, failed. He had used the money he inherited from Grandma Schryer to start this business, on his own, in the 1950s. Audrey and his other siblings were judgmental and never forgave this business failing. They shut him out. By the time he started a successful business in 1980, G and D Tool and Automation, there were few siblings left alive to see it. In this business he had a partner who did the wining and dining of customers. Alanson saw that the product was of high quality and delivered as ordered. It was a specialty business, not a production house. His last big job was an automated machine that painted parts, a piece of equipment he was very proud of.

Alanson was the black sheep of the family. It was a sore point that Fran and Howard did not invite Alanson on their Canadian fishing trips, nor did Fran and his family stop to see Alanson when they were in town to see Howard.

Alanson’s Children

Carol Alice (Schryer) De Puys born 16 Oct 1948

When Carol was young, Shirley invited her to come live with her and Buzz in Hawaii and attend the University of Hawaii. Alanson immediately said no. He was afraid that, like Shirley, Carol wouldn’t come back. Instead, Carol went to Northern Michigan University and studied elementary education. She went on to be an office manager in a machine and tool shop. Now retired, she works part-time at Eastern Michigan Bank.

Her daughter by her first marriage with Leonard Bell, Krista, (born 29 Oct 1971) works at the same bank as Carol but in a different branch. She is married to David Short who manages a lumber yard at a local super center. Carol’s daughter with her second husband, Henry De Puys, is Jessica (born 30 Jan 1976). She’s an assistant bank manager at Comerica and her husband Michael Enders is an engineer at Sumitomo.

Carol was very close to Aunt Audrey and through that relationship, and her own family knowledge, was extremely generous and helpful with this work. I thank her.

Carol saw her father as a serious and driven man, but he was able to relax and be something of a clown in the last years of his life.

Jerry (Gerald) Schryer born 7 Dec 1943, died 7 Jan 1981

All of Alanson’s sons, like himself, served in the armed forces. Jerry went to Vietnam.

In 1981 he died of liver cancer that he had contracted as a result of exposure to Agent Orange while serving in the Vietnam War. The VA continues to deny that this exposure was the cause of his illness. Some members of the family wanted to fight that determination but others did not.

After the army he worked as a tool maker until the last 15 months of his life. During the months leading up to his death he spread his faith at the hospital where he was treated.

Jerry’s first wife was Linda Mae Paxton. They married 10 July 1972 and she died 13 March 1999. They were high school sweethearts. They had two children, Amy (born 7 Dec 1974) and Alanson (born 14 Jan 1978). While Linda loved Jerry very much, she did not like the Schryer family.

Amy is a stay at home mom and has two daughters, Linda (born 27 Jan 1996) and Cora (born 27 Aug 1999), by her husband Joel Oostendorp.

Alanson is married to a woman named Deanna. Once his mother died in 1999 he sold the house and moved to Arizona. Like his mother, he does not care to have contact with the wider Schryer family.

Jerry later married JoAnn Stevens (born 9 Dec 1945) and had a daughter, Denise (born 22 Feb 1966). She has two daughters, Brandy (born 24 July 1993) and Jessica (born 20 Aug 1997), by her husband Michael Joseph Marzalec. She works in a bank.

Alan Frederick Schryer born 24 Sep 1953

Alan went to college for five years and then went into the Navy to serve on a nuclear ship, first to Europe and then to the Mediterranean. He spent his first five years aboard the U.S.S. Billfish. When Jerry died he put in for a transfer to be closer to Ron. The brothers served on the U.S.S. Enterprise, also a nuclear ship. He trained to work in nuclear power.

After being released from the navy, he worked at the Palasades nuclear power plant in South Haven for three or four years. After that he got his teaching certificate and taught for several years at a Christian school. When he quit there, he became an electrician. He also taught Sunday school in a bus ministry. He was part of a group that went to remote areas to teach to children who were unable to get to church any other way.

Alan and his wife Marteka had four children: James, born in 1986, who died by drowning on 17 Jul 2004, twins Sandra and Sarah born in 1990, and Gideon born in 1992.

Alan hasn’t worked in two years due to a brain tumor. He can care for himself but he can’t be left alone. Sandra has cerebral palsy and needs constant care; she is not able to go out on her own. Marteka cleans offices at night and cares for her family during the day. They go to a very caring church, Rosepark Baptist, and sometimes men will come to take Alan for the day, and women will come to care for Sandra so Marteka can have a respite break.

Sandra, Sarah and Gideon have all graduated from high school. Sarah and Gideon attend Hyles Anderson University in Indiana. Sarah wants to go to the mission field and Gideon wants to go into the ministry.

Ronald William Schryer born 8 Jun 1956

After his naval service on a nuclear ship, Ron went to work for Michigan Indiana Electric in Bridgeman, Michigan.

His wife Mary Ann suffers from a degenerative disease that affects the muscles and she is crippled. Their son Andrew (born 16 Jan 1981) lives in New York. He has the same disease as his mother, although it has shown up in him much earlier than either Mary Ann or Mary Ann’s father, who also has the illness. Andrew is currently unemployed.

HOWARD (4 Aug 1924) (William Arthur’s son)

Howard was born 4 Aug 1924. He married a strong-willed woman named Margaret Lossing. She worked for some time as a bookkeeper but was a homemaker after their daughter Janet was born. It is their niece Carol’s belief that all of William and Emeline’s sons married strong women due to their mother’s influence.

Howard served in the army during World War II on a general’s staff, scouting ahead in towns for a place for the general to stay. Howard was relegated to the ranks when the general discovered that Howard was booking the best places for himself and the second best for the general. Norm has a German officer’s luger pistol, a “prize of war,” care of Howard.

At one point, Howard stole the general’s Jeep and drove to the front lines to see his brother Alanson.

Howard was in the Battle of the Bulge and stationed in France. He also spent some time in Holland where he met Schryers who ran a hardware store; he stayed with them for awhile and received warm hospitality. He tested high enough to become a gunner but wanted to become a pilot. He never made it out of the infantry.

After the war, Howard was a policeman in Detroit but left the city in the late 1950s for Frasier and worked for GM.

Howard died of heart failure as a relatively young man. He put in a full day at the factory and then came home. He told Margaret he wasn’t feeling well and she said she’d make him some tea. By the time she brought it to him, he’d died of a heart attack. Margaret herself died of complications from cancer. They are buried a few hundred yards from Fran and Elaine in the Good Shepard section of the Cadillac Memorial Gardens cemetery in Clinton Township, Michigan.

Howard and Fran went fishing together every year at Kindiogami Lake in Ontario, Canada. They both enjoyed it a great deal. It was so remote that they had to be taken in by helicopter. All four of their grandparents were born in Canada so this is not a surprising vacation destination, although we tend to forget that Canadian connection now.

Howard and Margaret’s daughter, Janet, married John Donohue. Janet and John had no children. She worked in the mayor’s office for the city of Detroit as a young woman and has a college degree. She was in a serious car accident in 1982 and went into a home business making specialty children’s clothes. Today she does a great deal of charity work, particularly with unwed mothers, and is a successful gardener.

Janet told me of how, while Howard worked in the factory, he was teased a great deal on account of his strong faith. One day he put a man on the floor for it. That stopped the teasing.

Later Years

When William Arthur died in 1944, three of his children were at war. He had a small funeral. Emeline died in a nursing home after a long struggle with Type II diabetes. She would hide Pepsis under her bed and beg her family to bring her sweets. Diane remembers visiting Emeline in the nursing home on Sundays. All of Emeline’s children contributed to the cost of her care. We don’t know where either are buried.

Not every generation of the Schryer family is romantic. But it’s all the stories throughout the generations that make up who we are.

The Taylors

William Arthur’s first wife, Christina Taylor, mother of Davison and Margaret, was born 8 Jan 1877 and died 3 March 1909. She is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Flint with members of her father’s family (Genesee County Cemeteries volume 3). According to Aunt Audrey, Christina’s father, Robert A. M. Taylor (born 25 Dec 1853, died 25 May 1912), was a remittance man from Scotland. Perhaps coincidentally, he was a tailor by profession. Christina’s mother (also named Christina) was Scotch-English (1910 census). She was born 7 Nov 1853 and died 27 May 1931. Robert and Christina had at least nine children.

Christina and William Arthur married 16 May 1902 in Flint. He was 28 and she 25. Their first child, Davison Taylor Schryer, was born a year and a half later on 22 Oct 1903 and died in January 1962 in Hobbs, New Mexico.

On 22 Oct 1905, William Arthur and Christina’s second child, a daughter named Margaret, was born in Flint. Margaret grew up to marry Chris Palkow on 9 Oct 1926 and they had three sons. Margaret was much loved by the entire family.

Audrey Mae was the third child of William and Christina. Audrey Mae was born 6 April 1908 and died 12 Aug of the same year (age 4 months and 6 days) of an intestinal obstruction (Genesee County Death Records). She is buried with the many Schryers at Avondale cemetery in Flint. See the section on Joseph Schryer for plot details regarding Schryers buried at Avondale cemetery.

The Egans

Emeline’s father was Francis B. Egan Sr., after whom his son (“Uncle Frank”) was named, as well as Emeline’s son Fran Schryer, to whom this work is dedicated. The name continues as a middle name into the current generation for Michael (Gunther) Francis Schryer (son of Norm and Jan Schryer) and Silas Franklin Schryer (son of Tom and Charlotte Schryer).

Francis B. Egan Sr. was active in Republican politics and according to his obituary in the Detroit Free Press was “at one time one of the most widely known politicians in the state” (Detroit Free Press October 9, 1916, pg. 7). He eventually became the Deputy Secretary of State. He started life as a printer in Sarnia, Canada. According to one obituary, he worked for a time at the Detroit Free Press.

We know of at least two addresses for the Egans during the time he served in Lansing: 210 West Washington and 616 Ottawa Street. Both houses were just two blocks from the capitol building. In 2009 both houses had long been torn down and replaced with modern buildings. I walk by the West Washington street address often when I go to lunch; I work in downtown Lansing on Kalamazoo Street at the Library of Michigan.

Francis Egan married Emmaline Wright in Montreal and they had four children: Francis (born 1874), Ida (1879-1888), Elizabeth (1880-1888) and Emeline, our ancestor, born in Detroit on 28 Aug 1883. Emeline’s mother, Emmaline Wright, was the daughter of John Wright and Sarah Ann Robinson (born in England).

In 1888, while the family was living in Lansing, Emeline’s two sisters, aged about 8 and 9, died of scarlet fever within a few weeks of each other. They are buried beside one another at Mt. Hope Cemetery in Lansing. When their father died 28 years later he was buried beside them. There is space for another grave but there is no marker and the cemetery does not have records of any other Egans buried there. We don’t know where the two remaining children, Frank and Emeline, both of whom lived to an advanced age, are buried.

On a light note, in 1900 Francis Egan formed a secret club of which he was elected president. They called it the Washington Club. He said members were tired of the “namby-pamby methods of the Michigan club” (Detroit Free Press, Aug 1, 1900). He said club members intended to expand their organization in “every ward and precinct” of Detroit.

The paper reported: “There is to be another meeting of the club next Friday night for the adoption of a constitution and by-laws. Mr. Egan, however, refused to say where the meeting will be held as he stated it was to be a secret gathering.”

For a more serious look at his political career, please see the obituary below.

Francis Egan’s obituary from the Detroit Free Press 9 Oct 1916 p. 7 (1 pp.) reads:

Former Deputy Secretary of State Was Ill Four Months.

Was at One Time Prominent in

Republican and Labor Circles

Francis B. Egan, former deputy secretary of state, member of the state legislature and prominent Michigan Republican, died at the age of 70 years Sunday afternoon in his home at 331 Lincoln Avenue, after an illness of nearly four months.

At one time Mr. Egan was one of the most widely known politicians in the state and was prominently identified in state politics with Charles S. Hampton, defeated mayoral candidate. He was the first president of the Knights of Labor and was one of the organizers of the present Federation of Labor and was at one time president of that body.

Born in Newfoundland

Mr. Egan was born in St. John, Newfoundland October 3, 1946. He was educated in London, Ontario and learned the printer’s trade in Sarnia, Ontario. He came to Detroit in 1869 and worked as a printer on The Detroit Free Press for many years.

In 1885 Mr. Egan was elected to the legislature on the Republican workingman’s ticket and at once took rank among the members of that body as an effective debater. He introduced and carried through the Egan law – a measure which was intended to purge the metropolis of long standing abuses in electoral affairs by elimination of a certain element which was alleged to have controlled the polls.

Mr. Egan was also the author of the bill providing for the re-registration of voters in Detroit, which became a law: the bill abolishing contract labor in the state prisons and introduced many minor reformatory measures in the interests of organized labor. He was known as one of the more persistent advocates of labor interests in the history of the state

Decline Advancement

At one time a state paper proposed Mr. Egan as the right man for the nomination of the lieutenant-governor. He declined the honor replaying that the position was not one in which he could be of particular benefit to the workingmen.

Mr. Egan served at deputy commissioner of labor for several years. Later was connected with the water board and in the city hall.

He is survived by a widow and two children. Francis B. Egan Jr. and a daughter, Mrs. W. H. [sic] Schryer, both of Detroit. Funeral services will be held in the family home Tuesday evening at 7:30 o’clock and burial will be in Lansing Wednesday.

Francis Egan’s death certificate reads that he died of senility.