Davison Walker Schryer

b. 15 Jun 1849

d. 25 Apr 1877

Married: September 1869, Papineauville, Quebec, Canada

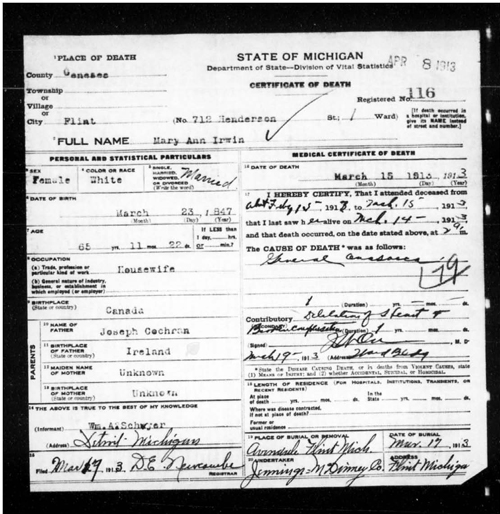

Mary Anne Schryer (nèe Corcoran)

b. 23 Mar 1847

d. 15 Mar 1913

Davison is the next in our family line, son of Joseph Schryer. Davison Walker Schryer and Mary Corcoran were born and married in Papineauville, Quebec. They immigrated to Flint, Michigan between 1869 and 1874 where their first child and our ancestor, William Arthur, was born 16 May 1874 (1880 U.S. census).

In 1876, according to the Flint City Directory, Davison and Mary were living at the north east corner of Wood and Root in the first ward of Flint. Davison was listed as a laborman. This included work on a railroad being built through Flint. Rail was a booming business. In 1849 there were 7,500 miles of track in the United States. By 1860 there were 30,000 miles (Beatty, p. 27).

According to Margaret (Schryer) Polkow, Davison’s niece, he was killed in an accident while working on the railroad. He died 25 April 1877 at the age of 28 (Genesee County Death Records). He was brought home on a cart, dead, to his wife. She was pregnant with their third child.

Seven months later, on 19 Nov 1877, she gave birth to a son and named him Davison Walker Jr., who was known as Wally. According to Aunt Audrey, Joseph helped raise William Arthur; they lived just a few miles away from one another.

In the 1880 U.S. census, three years after his death, Mary listed her occupation as washerwoman. Washing clothes was called “outwork” as it happened outside a factory or shop and was a common means of support for working class women. Long before the social security administration, widows had no state or federal means of support after the deaths of their husbands. Another common arrangement was to take in a boarder. As many as one in five households of this time period included a boarder (Mintz and Kellogg pp. 88-90). It should be noted that whatever her income, she was able to maintain the residence the family had shared when Davison was living.

Most of the neighborhood’s residents were born in Canada, England or New York (the opening of the Erie Canal in New York in 1825 contributed to much of the migration). It appears to have been a working- to middle-class area with most of the married women “keeping house” and many of the children “at school.” Some of their neighbors’ professions included carriage trimmer, telegraph operator, tailor, tinsmith, boarding house keeper, and workers at sawmills and hardware stores.

The 1890 U.S. census was destroyed in a fire or we might know more about how Mary fared in the decade after Davison’s death. Re-marriage was also common and Mary married George Simmonson, also born in Canada.

Mary (Corcoran) (Schryer) Simmonson married for a fourth time to Warren Irwin on 9 Sept 1902 in Pontiac. She died 15 March 1913 at the age of 66 after an illness of one year related to heart congestion. She is buried in Avondale Cemetery in Flint.

In 1894, William and Minnie were boarding together in Flint. William worked as a carriage trimmer, meaning he worked on the upholstery of horse-drawn carriages. Minnie worked as a seamstress and went on to be a forewoman. She died in December 1950 in Flint.

In 1996, my mother and I visited the Flint area where the family once lived. The home was long gone and the lot vacant. The economically devastated area was drug-infested with signs ordering no stopping or cruising.

In the 1900 census, Davison Jr. (Wally) was listed as a day laborman and later in life as a painter. By 1910 he had moved to Detroit where he married Maud Ensworth and had at least four children: Burtis, Onnolee, Irene, and Mary Annabelle (who died at the age of one from complications due to pneumonia [Michigan Death Records 1897-1920]).

Our extended family remained close. Onnolee signed her name in the guestbook at Fran and Elaine’s wedding.

There are three children, other than Mary, buried at the family plot at Avondale Cemetery in Flint: first, Audrey Mae, daughter of Christina and William Arthur. Next, an infant male and a one-year old named Ruth. William or Wally are possibly the parents of the male infant and Ruth, given the unmarried status of the rest of that generation of the family buried in that cemetery. There is no further family information about the possible parentage of these children.

By 1903, William was listed with his wife Christina A. Taylor, still working as a trimmer, residing at 326 Avon. By the age of 35 he was a widower. William returned to his mother’s home with his son Davison but census records do not show his daughter Margaret living with him. We know she came with him when he re-married to Emeline Egan.

The Corcorans

Mary (Corcoran) Schryer’s father reported in the 1851/2 Canadian census that he was 36 years of age, born in Ireland, and that the family was Catholic.

Audrey Schryer remembered that Mary was trained as a nurse, that she was a twin, and that she had been married before. She recalls that that first marriage produced three children, two of whom lived. Apparently, these children did not move to the United States with her. I have not been able to find confirmation of this previous family. Her first child by our ancestor Davison was born when she was 19 which makes Audrey’s story about three children from a previous marriage unlikely.

When I think about Mary, my second great-grandmother, I have to pause. She left her parents and her native country as a young woman. She adjusted to three husbands and raised at least three children. Maybe she knew the key to satisfaction in all life circumstances. Maybe she was the Oprah Winfrey of her neighborhood. I certainly hope that she was. And I hope she was strong. We know she raised at least one tough son – William Arthur.

Let’s take a look at what was happening in Davison and Mary’s new country.

The Gilded Age, 1865-1901

The Gilded Age, so coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, was characterized by a number of social and political events: industrialization; the flourishing and subsequent regulation of the so-called “robber barons” (such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan); the Reconstruction of the South; and the ballooning of the federal government. It was also the latter portion of the Victorian Age.

Industrialization

Chambers II, J. W. (1992). The tyranny of change: American in the Progressive Era: 1890-1920 (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Morris, C. R. (2005). The tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan invented the American supereconomy. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Socially and economically, the Industrial Revolution transformed nearly every aspect of life in the United States. It was more pronounced in the northern states and so was the wealth that industrialization brought. The U.S., from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to 1900, became the richest nation in the world. The British watched on in dismay. The U.S. “dominated world markets – not just in steel and oil but in wheat and cotton. It ran huge trade surpluses in goods, and was gaining preeminence in financial services. Its people were the most mobile, the most productive, the most inventive, and, on, average, the best educated” (Morris, xi).

Industrialization relied on the labor of immigrants. They worked in mining, petroleum, textiles, steel, in shipyards and in manufacturing of all kinds. Cities and towns were born from farming communities with factories and the populations of immigrants who worked in them.

Between 1870 and 1900, 11.2 million immigrants arrived in the United States, mostly from southern and eastern Europe. “Contrary to the well-established stereotype of the ‘huddled masses,’ the majority of the new immigrants, while poor, came not from the poorest classes but from the lower and lower-middle levels of their societies. These were not dispirited impoverished people, but typically strong, ambitious young men and women from overcrowded peasant villages” (Chambers, p. 11-12). Industrialization was dependent on these people, as much as it was on the great men who organized it and the strategies of economics and mechanization they employed.

But working conditions were harsh. Seven day work weeks were not unusual. Children were employed in dangerous positions. There was no “safety net” for workers injured on the job, or their families. Wages were sometimes lowered capriciously. The marketplace was running wild without much concern for those that labored to make the country a world-wide manufacturing empire.

There were many attempts on the parts of the workers to increase wages, improve conditions and reduce working hours. In 1886, in Chicago, the Haymarket Massacre occurred. A peaceable demonstration in favor of strike turned violent when a bomb exploded and eight police officers died, mostly by friendly fire. The archetype of the anarchist worker was born. Next was the Pullman Strike, led by Eugene V. Debs. Also a Chicago-based strike, it put rail traffic there to a stop. President Grover Cleveland ordered federal troops to put an end to the strike. Congress questioned him and the Supreme Court backed him, but it cost him the next presidential race.

The tycoons of the day were not as easily displaced.

Captains of Industry

Carnegie: U.S. Steel.

Rockefeller: Standard Oil.

J.P. Morgan: Financier and banker.

Jay Gould: Financier and railroads.

Cornelius Vanderbilt: Railroads.

John Jacob Aster: Real estate and fur.

James Buchanan Duke: Tobacco.

50% of U.S. wealth was concentrated in the hands of 1% of the population.

Opinion varies widely on these men. Did they enrich themselves on the backs of immigrants? Did the wealth they brought to the United States enhance the wealth of the nation in ways that improved the lives of nearly everyone, including poor workers? Were they entrepreneurs in the finest sense of the word? Wasn’t the American dream of building a better life for your children and descendents realized because of these men and the industry they brought – the inventions of products and creation of finance they can be credited for? Did they attempt to crush resistance from forces small and large, from the poor as well as the powerful? Were many of them criminals in the ethical as well as legal senses of the word? Did they manipulate market forces or were there attempts at self-regulation? Did their philanthropy bring some level of balance to their slash and burn model of laissez-faire economic success? Yes to all.

Let’s examine one of these tycoons: Andrew Carnegie. He was an immigrant himself who came from Scotland as a young child, the son of a hand-loom weaver. Carnegie started out as a factory bobbin boy – a classic rags to riches story. At 17 he found a mentor in Tom Scott, a railroad executive. Carnegie rose quickly, and to a very high position, in the railroad business, until steel caught his eye. “Carnegie was so spectacularly talented – with his extraordinary intelligence and dead-accurate Scots practically, his energy, his immense charm, his feline instinct for a deal – that he simply overmatched everyone else” and “It is no surprise that … of the great tycoons … none but Carnegie was so repellently smarmy” (Morris, p. 13-16).

He was not without his quirks. Carnegie didn’t marry until he was 51, inseparable, until then, from his mother.

I choose to focus on Carnegie because his philanthropic efforts built more than 2,500 libraries, most in the US, between 1883 and 1929. He built architecturally stunning library buildings with sharp, realistic standards of local support. More than half still serve as libraries from the smallest of communities to the nation’s largest cities, including New York and Pittsburgh. There are 31 Carnegie library branches in New York alone. Some original library buildings nationwide have been converted to other uses, such as historical societies and museums.

Almost every request for a public library was granted as long as the communities could meet Carnegie’s requirements of ongoing self-support for maintenance and collection development. Carnegie built the buildings, just as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation brought the initial waves of computer hardware and software to libraries across the nation.

Reconstruction and Ulysses S. Grant

Between 1869 and 1877, Ulysses S. Grant was president of the United States. As head of the victorious Union Army he was an obvious presidential contender and easily won both elections in which he sought the office. Unfortunately, he had little political acumen and appointed men, often military men, not appropriate to the power and responsibility of their positions. His terms were fraught with scandal (Tobias, 2010). Grant’s principal activity as president involved the Reconstruction of the South.

Grant enfranchised former slaves which changed the social and economic systems of the South. He used the U.S. Army, taxation and tariffs to increase federal influence and power in the South through the Military Reconstruction Act and other means.

In 1868, the 14th amendment passed, guaranteeing citizenship to everyone born in the United States except for Native Americans. In 1870, the 15th amendment was passed which granted all male citizens the right to vote. In 1877, Reconstruction officially ended. And in 1896, the “separate but equal” doctrine, officially establishing the Jim Crow laws, was affirmed by the Supreme Court in Plessy vs. Ferguson.

Following Reconstruction, literacy tests and poll taxes drastically reduced the number of “eligible” voters in Southern states. Most African Americans in the South lived in unabated agricultural poverty. Many of the goals of Reconstruction, as they applied to African Americans, were not met.

The Breadth of the Federal Government

Another result of the Civil War was the dramatic increase in the breadth and power of the government. The federal government became the nation’s largest employer during the war and this trend did not diminsh with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

“State capacities built steadily throughout the post-Reconstruction era. Congress created multiple new departments, bureaus, and programs, and federal civilian employment grew much more rapidly than population. Just as today, conflicts between political parties, the drama of electoral politics, and the vagaries of congressional lawmaking dominated the headlines. But the day-to-day activities of government were in the charge of administrative departments and bureaus. Operating under broad delegations of authority, administrators developed a rich internal law of administration that guided massive administrative adjudicatory activity and substantial regulatory action as well. Moreover, policy innovation at the legislative level depended heavily on the research and recommendations of existing administrative agencies. In short, if we look at legislative and administrative practice rather than at constitutional ideology or political rhetoric, we can see the emergence of a national administrative state and national administrative law before either had a name” (Mashaw, 2010).

The U.S. government, while sometimes considered ineffective by the public, engendered very high voter turnout. “In the last third of the century, the turnout of eligible voters reached 80 percent nationally and 95% in certain sharply divided states in the Midwest” (Chambers, p. 39).

Education in the 19th Century

From: Rury, J. (1995). Education and Social Change: Themes in the History of American Schooling. Mahwah, New Jersey.

The Gilded Age had a significant impact on education, especially in cities. On average, more people attended school and for longer periods of time. It was estimated that in 1800 the average child received 210 days of formal education. By 1850 that figure doubled to over 420 and by 1900 it was 1,050 (half of what it was to become by 2000). But these numbers varied a great deal among social classes. Immigrants, particularly those working in factories, were often employed as children or teenagers and received less schooling.

Educational theory was undergoing a shift as well. School came to be seen as preparation for work as well as for life. “The ‘habits’ of industriousness and responsibility, along with essential skills of literacy, numerical calculation and knowledge of history, geography and other subjects” (Rury, p. 64) became the norm.

Other Notable Events

The Gilded Age saw many other developments as well.

Thomas Edison invented, among other things, the first working phonograph, motion picture camera, and successful electric lighting system. By 1876, Alexander Graham Bell had created a successful telephone. He was an immigrant himself, born in Scotland. In 1876, 10 million visitors to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia were exposed to these inventions “but the hit of the exposition was the gigantic steam engine built by George Corliss: 45 feet high, 52 tons in weight, 30 feet in diameter, with two 10-foot pistons rotating 36 times per minute, and capable of powering 13 acres of the exhibits’ machinery” (Hunt).

Manifest Destiny was considered complete. The Indian Wars ended in 1890 at Wounded Knee, South Dakota where U.S. soldiers massacred a village of Lakota Sioux Indians. The U.S. government began a series of endeavors to “Americanize” Native peoples by turning them into farmers or requiring them to abandon their Native methods of life. These endeavors, often coercive and corrupt, were, for the most part, dismal failures (Chambers, p. 8).

And last but not least, baseball was coined the “national pastime.” The first professional team was established in 1869: the Cincinnati Red Stockings.