Nicholas Schryer

b. unknown

d. unknown

Married: date unknown

Mary Schryer (nèe Eastwood)

b. unknown

d. unknown

Nicholas Schryer and Mary Eastwood are Francis William Schryer’s earliest known patrilineal ancestors.

We know that Nicholas and Mary lived in Schaghticoke, New York, near Albany, at the time of the Revolutionary War. After that, they lived in Highgate, Vermont, near the Canadian border. Several of Nicholas’s children, including our ancestor, Simon, and his brother, Abraham, immigrated to Canada as adults and many of the descendents of Nicholas and Mary are Canadian today. We don’t know whether Nicholas himself emigrated from Europe or was born in the colonies. Hopefully, as more early local historical records are located and made available, we will be able to answer more questions and make the next generational leap. For now, let’s begin with what we know about Nicholas and Mary.

Nicholas and Mary had at least four children. The oldest of the boys, our ancestor Simon, married a woman of English ancestry. Another son, Abraham John, married a French Canadian woman and converted to Catholicism. We don’t have marriage records for Nicholas and Mary’s other two known children, Isaac and Cattrina.

The name “Schryer” – meaning “crier” or “town crier” – is German and multiple members of our family listed their heritage as German in the 1871 Canadian census and other records. But a hundred years earlier, in 1781, Nicholas and Mary baptized two of their children in the Dutch Reformed Church. Below I talk about the Dutch Reformed Church and its historic relationship to Germany.

The Dutch Reformed Church

From De Jong, Gerald Francis. The Dutch Reformed Church in the American Colonies. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978.

and

Klopott, Rita Beth. “The History of the town of Schaghticoke, New York 1676-1855.” State University of New York at Albany, 1981.

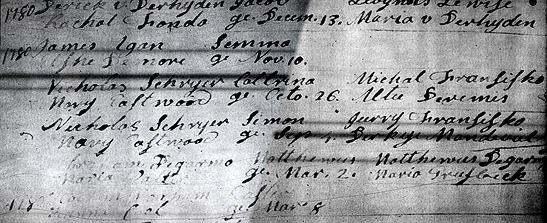

Nicholas and Mary baptized two children in the Dutch Reformed church at Schaghticoke, New York: Simon, on 4 Sept 1781, and Cattrina on 26 October(?) 1781. The dates are awkward, but it’s possible that Simon and Cattrina were twins born on the earlier date and baptized on the latter, or that they were born in different years but baptized at the same time. Simon’s birth date has been confirmed as 4 Sept 1781 in other sources.

The first Dutch Reformed Church in North America was established in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in 1628. One hundred fifty years later, in 1776, there were nearly one hundred Reformed congregations in the colonies. This is despite the fact that Dutch immigration was very light after New Netherland surrendered to the British in 1664. The Dutch treated their American colonies as economic enterprises (relying on the fur trade) rather than places of settlement, and they did not provide for their defense. When the English conquered Dutch holdings, New Netherland was renamed New York. Fort Orange, another Dutch stronghold, was renamed Albany.

Under English rule, the Dutch colonists retained the freedom to worship. Of course, other religious denominations had the same freedom and this led to some Dutch mutterings. Local rule was established under the British. Lands, taxes and duties were set aside for the functioning of the local churches, including caring for the poor. Interestingly, these officially-established “community churches” were determined by population numbers and members of minority congregations initially found themselves obligated to support Dutch Reformed Churches through taxation. For obvious reasons, this particular aspect of local church control did not continue for very long. Also, due to their numbers, Dutch settlers, notably Dutch ministers, continued to have a strong political influence in the colony of New York. The English allowed religious freedom, but demanded secular obedience with the goal of decreasing unrest and increasing profits from the colony.

The swell in the number of congregations despite the light immigration from Holland was due to a strong birth rate and the addition to the church of members of people of different nationalities, notably French Huguenots and German Palatines. The Palatines arrived in greatest numbers between 1664 and 1714.

The Dutch Reformed Church has its roots in the Protestant teachings of John Calvin and other reformers of the sixteenth century. Many of the regulations that governed the colonial church life of Nicholas and Mary in the late 1700s were established in 1563 in a set of laws known as the Heidelberg Catechism.

The Palatines of the Rhine Valley had a strong Calvinist background and both they and the Dutch Reformers adhered to the Heidelberg Catechism. These Calvinist groups had friendly relations in Europe and when German Palatines began to immigrate to the colonies, many took up residence in Dutch-dominated New York. Letters home to Germany encouraged additional immigration.

Reformed services were conducted in Dutch and two-thirds of ministers came directly from Holland. Ministerial salaries varied, but were highest in New York, where ministers were paid quarterly. Ministers also received a house, firewood, a garden or even a small amount of farmland, and free pasturage. They supplemented their incomes through officiating at events such as weddings and funerals and were sometimes paid in goods and services.

Reformed congregations were not puritanical. In particular, liquor was a staple at social events and ministers drank along with their congregations both in private and public. Funerals were often lavish affairs with food and drink expenses often surpassing the costs of the funeral itself. The church was even known to pay the funeral liquor expenses for paupers. Redeeming to the modern eye, colonial Reformers had a reputation for being frugal in other matters.

Even small churches held two services on Sundays during three seasons of the year, but often just one during the winter months. Services generally lasted two hours, with an hour set aside for a sermon whose time was measured with an hourglass at the front of the church. In between the two services, congregants would visit; for some this may have been the only time during the week that they saw one another. The church was the only community building in Schaghticoke (also the only church); there was no square, city center or even a store, although there was at least one tavern where town meetings would take place. Albany, 18 miles away, was still considered “town” for the residents, and it served as their legal and political center.

Later in his life, Simon was to bury a child at a Presbyterian church and also to report himself as a Universalist. He baptized at least two of his children as Catholics. Later, in Canadian census records, he reported his wife and all of his children as Catholic while he himself had “pas” (no) religion.

Life in Schaghticoke in the Later Eighteenth Century

Klopott, R. Beth. “The History of the Town of Schaghticoke, New York 1676-1855.” State University of New York at Albany, 1981.

What were the communities that Nicholas and Mary lived in like? In 1781 they were in Schaghticoke, New York, an outgrowth of Albany.

Schaghticoke lay on the east side of the Hudson River 18 miles from Albany; it was 2 miles wide and fourteen miles long. The town was established by Albany for its support in 1707. Farms (usually in 60-acre increments) were sold or leased to settlers and rent in the form of bushels of wheat and 2 fowls were required yearly. There exists a record of Nicholas Schryer paying his taxes in 1779 (Rensselaer County Tax Lists, 1779, Schaghticoke, courtesy Mike Schryer).

Wheat was the most important crop in the region and was used as currency at shops in Albany and the nearby town of Lansingburgh. Rents were often not paid in full and they were not required at all during time of war, when Albany needed the income most. There was no known industry in early Schaghticoke; it was a farming community.

The name Schaghticoke came from the group of Native Americans who were encouraged to take up residence to form a physical buffer from hostile French and Native American forces that threatened Albany. As the town began to rent the land to settlers, Native American residency was discouraged and all of the Schaghticoke Indians had left the area by 1754.

While Nicholas and his family had left for Highgate, Vermont five to six years before 1795, a census of Schaghticoke at that time showed 772 males, 688 females and 130 slaves. Nearly one in 12 residents was a slave. The number of freehold farms valued at over 100 pounds was 32% of total property, freeholds valued at 20 pounds were 34% and renters made up the remaining 34%. Unfortunately, we don’t know the size of Nicholas’s farm.

Political History

Klopott, R. Beth. “The History of the town of Schaghticoke, New York 1676-1855.” State University of New York at Albany, 1981.

and

Ferguson, Will. Canadian History for Dummies. Toronto: CDG Books Canada, 2000.

Nicholas and Mary lived in a time before the United States and Canada separated themselves into two distinct nations. The continent of North America was in the process of being settled by Europeans and divided amongst European powers. There were many conflicts concerning power, settlement, land and profits.

The war immediately prior to the Revolutionary War was the Seven Years’ War (actually, it lasted nine years, 1754-1763) and was known in the United States as the French and Indian War. The conflict was part of the on-going international power struggle between the British and French and was ended by the Treaty of Paris of 1763. The French ceded almost all of their territory in North America to the British although they maintained a strong cultural influence in Canada that persists to this day (Ferguson, pp. 119-136).

Two years after the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War, in 1775, as the United States prepared to fight its own war with Britain, the Continental Congress approved an invasion of Canada and attacked both Montreal (under Richard Montgomery) and Quebec City (under the command of none other than Benedict Arnold). The hope was to increase the territory that was to become the United States. While the attack on Montreal was successful, the attack on Quebec was a failure and the Americans withdrew on 2 July 1776. When the Continental Congress declared independence for the United States two days later they did not do so on behalf of any portion of what today is Canada. A few years later, Canada divided itself along cultural/linguistic lines into what would become Ontario and what would remain Quebec.

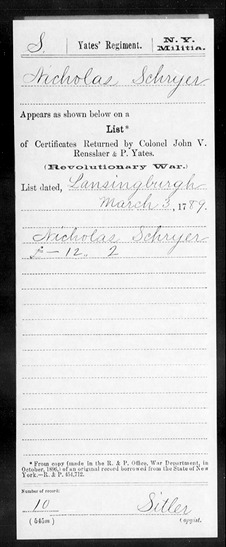

During the Revolutionary War, many residents of Schaghticoke moved from their farms into Albany and relative safety. Schaghticoke was partially ravaged by General John Burgoyne’s army in 1777. Adult males were allowed to join the Continental Army and receive rations for themselves and their families. The residents of Schaghticoke and Albany were primarily patriotic to the developing United States and loyalist incidents were negligible. Nicholas served in the 14th militia of the Revolutionary War out of Albany and appears here as an enlisted man under Colonel Peter Yates:

In 1781, Colonel Peter Yates and his Fourteenth Militia Regiment were stationed in Schaghticoke. Yates’s force was only 80 strong and his purpose was to suppress insurrection on the part of New Yorkers and quell riots initiated by people attempting to establish the state of Vermont.

The Vermont controversy was the greatest political challenge the community faced. The area between New York and New Hampshire was the cause of many legal maneuverings on both sides of the Atlantic. Eventually, violence erupted and some people living in the disputed Vermont territory began raiding areas of New York including towns in the county of Albany.

The U.S. government initially refused to act so as not to jeopardize the support of any party for the new Union. In 1781 the Cambridge Convention was held in Cambridge, New York and attended by representatives of ten towns in the disputed region, including Schaghticoke. These representatives recognized Vermont as a unique state and pledged their allegiance to it. This did not settle the matter locally.

At one point during the conflict, 200 men from Bennington, Vermont, rioted in Schaghticoke. The Albany County Sheriff Ten Broeck and part of Yates’s militia took several of the rioters prisoner. This was the last violence perpetrated by would-be Vermonters. The dispute was finally taken up by the U.S. Congress who debated for seven years before they made Vermont the 14th state in 1790, balancing this non-slave holding state with Kentucky.

While some of the men of Schaghticoke, including Nicholas, according to his time of service, were active in the dispute with would-be Vermonters, others were active in the Revolutionary War itself. On Oct 20, 1775 Johannis Knickerbacker of Schaghticoke was commissioned Colonel of the 14th Regiment. The militia unit then guarded the district from loyalist activities. A substantial number of men in Schaghticoke served during the Revolutionary War.

Nicholas and his family, whatever their political leanings, moved 200 miles from Schaghticoke, New York to Highgate Vermont, on the border of Canada, by 1790 (Nicholas Scrior [sic] Household, 1790 U.S. Census).

Life in Highgate, Vermont at the turn of the Nineteenth Century

Highgate was a much smaller community than Schaghticoke; only 17 households were recorded in the 1790 census with a total of 103 people. Nicholas’s household consisted of one adult male, three males under the age of 16, and four females, none of them slaves. These people could be children, extended family members, servants, boarders or others. Their relationship to the head of the household is not recorded.

On 18 Jan 1791 Nicholas and Mary had a son, Abraham John. His birth was registered with the town on 3 Sept 1795 at which time the birth of another son was also registered, Isaac, born 17 Dec, 1794.

Family Life

Mintz, Steven, and Susan Kellogg. Domestic revolutions: A social history of American family life. New York: Collier Macmillan, 1988.

and

Calvert, Karin. “Children in the house, 1890-1930.” In American home life, 1880-1930: A Social history of spaces and services, edited by Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth, 75-93. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

In the early years of the American colonies, the family was based on what is called the economic model. Parents chose spouses for their children based on the suitability of each partner in economic terms. The family was viewed as a micro-economy run by the husband and father. Parents had a great deal of control over their children’s lives well into what we consider adulthood today.

But literature of the period surrounding the Revolutionary War was rejecting this model and calling for reciprocated love and compatibility as a basis for marriage. A model based on affection and esteem grew more and more popular in the decades before Nicholas and Mary’s marriage. This mode of partnership was referred to as the companionate, rather than economic, model.

In the companionate model, beliefs about appropriate child rearing techniques changed also. Instead of simply instilling obedience to authority, parents were called on to “develop a child’s conscience and self-government.” Infants’ limbs and bodies were often swaddled in long strips of linen to encourage straight and proper growth. Wooden “walking stools” with wheels but not seats were popular to encourage early walking. Children’s clothing during the Revolutionary Period was simply adult patterns on a reduced scale. As soon as they could walk, girls wore petticoats and corsets to promote good posture. There were few toys made specifically for children.

The freedom of childhood ended at the age of seven when boys and girls started school, work or apprenticeships, at which point boys gave up long gowns for knee.

Everyday Life

Langdon, William Chauncy. Everyday things in American life: 1607-1776. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, ltd., 1937.

and

Langdon, William Chauncy. Everyday things in American life: 1776-1876. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, ltd., 1941.

and

Barrett, Tracy. Growing up in Colonial America. Brookfield, Conn: Millbrook Press, 1995.

The architecture of Albany (and Schaghticoke by extrapolation) was Dutch and introduced a strikingly useful piece of “extra” roofing that created what we now know as the front porch. This allowed for a comfortable place for visiting with neighbors and others without the formality of an in-home visit.

Eating utensils of the time were making the transformation from wood to pewter.

There were four newspapers operating in New York during the Revolutionary War but we do not know whether Nicholas was literate. Religious literacy – the ability to read the bible – was common in Colonial America. What we think of as literacy today – learning to both read and write in a secular environment became stronger during the period 1750 – 1800.

Women in particular, but men also, married earlier than their European counterparts. They also had a higher birthrate – on average one child every other year until the woman’s late thirties or early forties. Approximately one quarter of children born in Colonial America during this period did not live to see adulthood and of those that lived to the age of five, half had lost at least one parent.

Next we’ll talk about the two children of Nicholas and Mary that we know the most about, Simon, our ancestor, and Abraham, his brother.

I would like to thank you for this excellent research. I’m a descendant of this family. My grand-mother was Juliette Schryer, daughter of Clément Schryer. He was the son of Augustin Schryer. Himself son of Abraham John.

I’m living in Papineauville where Augustin and many other Schryer are buried.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am also a descendant of this family. My family name is Scraire from the Schryer who married Angelique Bonneau and come to Montréal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this research. I’m the great-granddaughter of Françoise Schryer, daughter of Clement Schryer, son of Augustin Schryer.

Despite everything I can find, I can’t confirm Abraham or Nicholas’ religion. Shreier/Schryer is after all a Jewish surname. I know Abraham converted to Catholicism but we don’t know what was his faith before his conversion. Would you happen to know the answer? Thanks.

LikeLike

Hi Jessica, I don’t know what faith Nicholas was born into. Try asking family genealogist Jeremy Schryer at jschryer@yahoo.com

LikeLike

The branch that went through Schaghticoke was Dutch Reform, right?

Tom

LikeLike

I have not heard that Schryer was a Jewish surname and it’s true that Nicholas and Mary baptized at least two of their children and in the Dutch Reformed Church.

LikeLike

The origin myth that circulated amongst my relatives was that my Schryer family was of Jewish descent, more specifically Iberian/Italian Jews that fled persecution and went to what is now Germany. The near totality of people in my family tree are of French descent except my Schryer ancestors who have a German surname, yet an autosomal DNA test showed I was 39% Southern European and 1% European Jewish spanning from Portugal, Spain and Italy. I have trouble believing this was pure luck of the draw. I had the results revified with another DNA lab and got the same results. Most Jews that came to the American colonies were Dutch Sephardic of Iberian origin so until I have solid proof showing otherwise I’ll consider the hypothesis of some Schryers converting to Christianity plausible. I’d love for more information on this if anyone has some.

Stephane Viau-Schryer

Montreal, Canada

sviaudstc@gmail.com

LikeLike

I am the great-grand-daughter of Lucie Marie Schryer, { daughter of Augustin Schryer 1830-1907 & Marceline Montpetit} who married Zéphir Chartrand. Thank you for clarifying the German roots in my DNA.

LikeLike

I am just working my family tree and Abraham Shryer was part of it. I had no clue my heritage was from Germany. This is unreal! I am just discovering so many amazing things but Im also afraid of what I may find. If any of you know more about our history I would love to hear some of my history!

LikeLike

Nicholas Schryer B: 18 Jan 1750 Highgate, Franklin, Vermont USA Bap: 22 June 1755 Albany NY D: 1800 Vermont, USA & married in 1780? Marie / Mary Eastwood B: 1740/42 D: 1753 ?

They lived in Schaghticoke, NY near Albany. In 1790, they lived in Highgate, Vermont Near the Canadian border near Philipsburg, Quebec. Nicholas served in the 14th militia of the Revolutionary War out of Albany and appears as an enlisted man under Colonel Peter Yates. (I have an e-copy of document) List dated Lansingburg March 3, 1789 He then served in the Incorporated Militia of Montreal = Last name written as Scrier, 5th Battalion Nicholas emigrated to Canada ca 1808? with Abraham? and settled in la “Petite Nation Seigneurie” now named Papineauville {1826 Louis J. Papineau mentions:” Schryar who works at the Mill…”} He is a carpenter.

Jonas B: 1781 ??? Vermont (Dutch parentage) D: 22 Aug 1862 Dundee, County of Beauharnois QC & Mary-Ann “Polly” Aubrey B: 1790/91? Alburg Vermont USA D: 18 Apr 1875 Dundee, Beauharnois, QC = 13 children (Washington 1825-1912, Amanda 1820-1856, James 1837-1893, Levi 1839-1890, Almira 1814-1902, Emily 1836-?, George 1817-1864, Edward 1814-?, William 1829-1906, John 1824-?, Nicholas 1815-1891, Franklin 1827-1910, Melissa 1834-1885) < – > Simon (Sr) Schryer B: ??? Bap 4 Sept 1781 Schaghticoke NY USA Dutch Reformed Church, Rensselaer NY D: 25 mai 1870 Petite Nation / Papineauville. Married a woman of English ancestry. Cattrina Schryer B: ??? Bap: 26 oct 1781 Dutch Reformed Church, Schaghticoke, Rensselaer County, NY. Don’t know if they stayed in the USA Abraham John Abram Schryer B: 18 jan 1791 Highgate, Franklin, Vermont USA (His birth was registered with the town on 3 sept 1795, at the same time as Isaac’s B: 17 Dec 1794 !) Bap Catholique: 25 Aug 1816 Montreal QC (1 day before his marriage, shoemaker, about 25 yrs 1/2, names of parents confirmed. D: 18 avr 1867 Clarence Creek ON Isaac B: 17 dec 1794 Highgate Vermont D: ?

LikeLike